Records aside, the Raleigh-Sturmey-Archer Team of 1936-40 represented the apogee of classic British road cycle sport in its truest pre-war form: the individual long distance time trial, the "R.R.A." record runs, the battle of man and machine against time and distance on open roads and in all conditions; the era of all-black kit, U-Win tights, Alpaca jackets, waxed hair, and roadside helpers in plus-fours offering up feeding bottles in the early morning mist.

The Team, managers and riders alike, were all "clubmen" and proven champions-- "stayers"-- of the time trial circuit of the 1920s-30s. Charles Marshall, Charlie Davey, Sid Ferris, Bert James, Charles Holland and Tommy Godwin represented a pool of talent and sporting achievement unsurpassed in British road cycling. Instead of a Tour of Britain, there was the annual contest for British Best All Rounder (the fastest overall speed in the classic time trial events in a particular year) and the Road Records Association (R.R.A.) long distance records. It was in the later field of competition that the Raleigh men thrived, coming to hold 9 of the 15 R.R.A. records between 1937-39. One, Godwin's all-time mileage record set in May 1940, and the last for Raleigh/Sturmey Archer, remains uniquely unbroken to this day.

The Team, managers and riders alike, were all "clubmen" and proven champions-- "stayers"-- of the time trial circuit of the 1920s-30s. Charles Marshall, Charlie Davey, Sid Ferris, Bert James, Charles Holland and Tommy Godwin represented a pool of talent and sporting achievement unsurpassed in British road cycling. Instead of a Tour of Britain, there was the annual contest for British Best All Rounder (the fastest overall speed in the classic time trial events in a particular year) and the Road Records Association (R.R.A.) long distance records. It was in the later field of competition that the Raleigh men thrived, coming to hold 9 of the 15 R.R.A. records between 1937-39. One, Godwin's all-time mileage record set in May 1940, and the last for Raleigh/Sturmey Archer, remains uniquely unbroken to this day.

In the mid 1930s, R.R.A. records were falling like nine pins under an onslaught by Frank Southall (then the greatest All-Rounder in Britain) riding for Hercules with the new three-speed Cyclo derailleur. He won most of the medium distance records including three set by Charles Marshall. In addition, the great Hubert Opperman of Australia came to Britain and quickly broke the Land's End-John o'Groats, London-Bath-London and 24-hour records in 1935. An Australian riding for B.S.A. with a Cyclo derailleur, he represented a triple threat to Raleigh/Sturmey-Archer. Determined to restore the records to Britain and to demonstrate the superiority of the new close-ratio hub gears he had helped to develop, Charles Marshall, then the Works Director for Sturmey-Archer, laid plans in early 1936 for a new professional team sponsored by both companies.

CHARLES MARSHALL

Manager, Sturmey-Archer Works/Team Director

Vegetarian Cycling & Athletic Club

The dean of Racing Raleighs was Charles Marshall through whose singular enthusiasm for the marque and hub gear not only formed the foundations for the Raleigh/Sturmey-Archer team, but inspired him to personally create and supervise it.

Charles Marshall was, first and foremost, a road cyclist of proven and record breaking ability himself. A passionate vegetarian, he joined the Vegetarian Cycling & Athletic Club around 1925 and quickly excelled throughout the inter-war heyday of the classic time trial and came to dominate the North Road 100. In 1928, he was part of the British Cycling Team at the Olympic Games in Amsterdam, winning a Silver Medal. On 8 July 1931, Marshall set a new R.R.A. record for London-Bath and back of 10 hours 39 mins. 54 seconds on a Raleigh Record with a Sturmey-Archer K three-speed hub that he personally had tweaked to give closer ratios.

Charles Marshall was, first and foremost, a road cyclist of proven and record breaking ability himself. A passionate vegetarian, he joined the Vegetarian Cycling & Athletic Club around 1925 and quickly excelled throughout the inter-war heyday of the classic time trial and came to dominate the North Road 100. In 1928, he was part of the British Cycling Team at the Olympic Games in Amsterdam, winning a Silver Medal. On 8 July 1931, Marshall set a new R.R.A. record for London-Bath and back of 10 hours 39 mins. 54 seconds on a Raleigh Record with a Sturmey-Archer K three-speed hub that he personally had tweaked to give closer ratios.

To Marshall goes much of the early credit in developing close-ratio hub gears for racing and he eventually became Manager of Sturmey-Archer's Works Department. He went on to recruit Reg Harris for Raleigh in 1948 and took an active hand in the design and specification not only of the special machines for him, but all of Raleigh's lightweights for a quarter of a century. Marshall held patents on several innovative cycling components including the Sturmey-Archer "trigger" shifter and quick-release mudguard fittings. Finally, he wrote many articles expounding the vegetarian diet, fitness and training regimes for cyclists.

It was Marshall's unique expertise in racing, bicycle and hub gear technology that led him to put together a new professional racing team in 1936 that had, as its chief aim, the proving and the promotion of the new range of hub gears that he and Sturmey-Archer's William Brown designed. Moreover, his active participation in the VC&AC gave him the personal contacts with some of the top riders of what was arguably the leading cycling club in Britain at the time. Indeed, it could be said that the Raleigh/Sturmey-Archer squad was really just a professional off-shoot of the VC&AC for, of its stable of top riders, all but one was a vegetarian and three were club members at various times.

Raleigh/Sturmey-Archer Team Manager

Vegetarian Cycle & Athletic Club/Addiscombe CC

It may have only been a coincidence that Raleigh/Sturmey-Archer announced at the end of September 1937, right at the time of Ferris's first record run that was disqualified for a R.R.A. rules violation, the appointment of Charlie Davey as the team manager effective in February 1938. From then on, the team would never fall afoul of rules or technicalities and be recognised as one of the best organised and managed in the sport.

There was no finer organizer, trainer or manager of competitive road cycling than "Mr. Davey" who managed F.W. Southall's record rides in 1935 and was latterly with Aberdale Cycles, Ltd., and brought with him the experience of an accomplished cyclist himself.

Like Marshall, Davey was an icon of the VC&AC, just of an earlier generation, first joining the club in 1910 and quickly making his mark. That year he set a new club record for the '100' of 5.6.22. And like Marshall, Davey was an Olympian, representing Great Britain in the 1912 Stockholm Games, clocking 11.47.06 in a 200-mile time trial. After serving in the Royal Naval Air Service in the First World War, Davey returned to track and road cycling. All told, he broke seven R.R.A. records between 1914 and 1926 as well as the 24-hour tandem paced track record, and won open time trial events from 50 miles to 24 hours. Turning professional in 1923 for New Hudson Cycles and the following year for Armstrong Cycles, he competed for more R.R.A. records and set a new mark for Land's End to London of 17 hrs. 29 mins. In the late 1920s, Davey even designed and built his own line of racing bikes in Croydon. Aged 40, Davey returned to competitive cycling and bested the London to Portsmouth and back record by 12 minutes and set the London to Bath and back record at 11h 47m 52s.

Davey wrote numerous articles and treatises on cycle training, fitness and regimens and, as a confirmed vegetarian, uniquely appreciated the diet requirements of his fellow non meat eaters on the team. He was uniquely qualified in the intricate route planning that went into R.R.A. record breaking not to mention the personal experience to know when to retire an attempt when the weather, traffic or other conditions were not suitable. Davey's "finest hour" was, in fact, a great many of them, in succession, when he was personal manager for team member Tommy Godwin's world's mileage record for Raleigh/Sturmey-Archer from May 1939-May 1940.

|

| Charlie Davey contributed this article to Cycling on 28 April 1937 on his training programme for Ferris and James. credit: Cycling, courtesy Peter Jourdain. |

As manager, Davey had to co-ordinate and integrate the distinct training habits and routines of his three riders as described in the Nottingham Journal 19 April 1937:

Sid Ferris, Bert James of Nottingham, and Charles Holland, the three famous racing and record breaking cyclists, are already in training for their attacks on the R.R.A. records in the forthcoming season.

Actually James has been training since the beginning of the year, but Ferris and Holland have now also commenced their own particular routine in preparation for their first attempts.

The three champions have surprisingly varied ideas and methods of training. Ferris and James are both vegetarians, and as such train on a strictly meatless diet.

But whereas Ferris believes in various forms of exercise apart from cycling and is always wary of the danger of getting stale James believes in cycling, cycling and still cycling as the ideal training method. For him there is apparently no danger of getting bored or stale-- he is scarcely ever off the saddle.

Holland, on the other hand, is not a vegetarian. He take a more or less normal diet while training. For exercise, like James, he sticks to cycling, but is like Ferris in guarding against over-training by not setting himself a too rigid discipline.

SIDNEY (Sid) HERBERT FERRIS (1908-1993)

Vegetarian Cycling & Athletic Club

It was no surprise when the first man recruited by Charles Marshall on 6 October 1936 to the Sturmey-Archer Team was his fellow club member, Sidney "Sid" Ferris. Ferris was then one of the top long distance time trialling men in Britain and a perfect choice to tackle the longer R.R.A. records recently won by Opperman.

It's worth noting that in those days revoking one's amateur status as a competitive cyclist and signing on as a professional was very much a "crossing the Rubicon" for, under the stringent rules then prevailing, once a professional, even accepting any endorsement or sponsorship from a commercial entity, it was almost impossible to revert to amateur status or compete in what was then an overwhelming amateur sport. So, the candidates that Marshall considered were all men at the peak of their amateur careers and around 30 years old, far older than today. For the sponsor, it meant tapping their talent in a few years and for the professional, it meant earning enough to make it worth the rest of their cycling career.

Sid Ferris was born into a cycling family, his parents running a cycle business in Hounslow and his brother, Harry, was an accomplished cyclist in his own right and was with, as Sid, in the Vegetarian C&AC. He, too, ran his own bike shop, Ferris Cycles, in Hounslow, specialising in custom designed racing frames

Sid Ferris joined the VC&AC in the 1920s and proved one of the club's "cracks" especially on the longer time trials like the North Road 24 Hours which he won three times in succession in 1932, 1933 and 1934. In 1930 and 1932 Ferris was on the VC&AC team that won the British All Rounder competition and was ranked 11th in all British amateurs in 1933.

Ferris's successes are all the remarkable in that he had only one eye, losing his left eye in a childhood accident and his eye patch became an instant trademark on the time trial circuit. His stamina was his hallmark as was his prowess, despite his eyesight, in night riding. In Ferris was the "stayer" that formed the linchpin of Raleigh's record breaking efforts to come.

According to Raleigh: Past and Presence of an Iconic Bicycle Brand (Hadland), the terms Raleigh gave Ferris included 1) a permanent job at Raleigh at £4.10.0 a week, regardless of records won, and increasing to £7 during road training for record attempts; 2) a £500 bonus for each of the End-to-End and 1,000-miles records if won; and 3) a bonus of £200 each for any other records of 200 miles or more.

According to Raleigh: Past and Presence of an Iconic Bicycle Brand (Hadland), the terms Raleigh gave Ferris included 1) a permanent job at Raleigh at £4.10.0 a week, regardless of records won, and increasing to £7 during road training for record attempts; 2) a £500 bonus for each of the End-to-End and 1,000-miles records if won; and 3) a bonus of £200 each for any other records of 200 miles or more.

|

| Ferris as portrayed in a series in Cycling "How Stars Train", 29 January 1939. credit: Cycling, courtesy Peter Jourdain |

HERBERT (Bert) JAMES (b.1906)

Vegetarian Cycling & Athletic Club

A perfect compliment to "stayer" Sid Ferris, Herbert "Bert" James was the quintessential "speedman" who excelled at time trials no longer than 50 miles. Yet, his greatest victory for Raleigh Sturmey-Archer who signed him in mid October 1936, was breaking the record for the "100" and it remained unbroken for another 21 years. And ironically, James never broke the R.R.A. for the "50" which was his specialty as an amateur.

Born in Llanbradach, Wales, James started cycle racing in 1926, clocking 1.16.25 for a "25". He joined the Newport and District Wheelers in 1927 and three years later the Oxford City Road Club. By the time he joined the ranks of the VC&AC in 1934, he was already one of Britain's best time trialists and only added to the laurels being heaped aplenty on the all conquering Vegetarians. That year he placed third in the British Best All Rounder classification, was 5th the following and missed being 1st by fraction in 1936 and beaten to it by future teammate Charles Holland.

The proverbial pocket rocket, James was but 5 ft. 6 ins. tall and weighed barely 9 stone 4 lbs.. He rode his 21" RRAs, usually painted in handsome light metallic blue with contrasting trim, "flat out" with his red-haired head dipping lower and lower over the 'bars as he got into his stride. Like Ken Joy after the war, his form and riding style was the acme of tester prowess and elegance. Cycling, in particular, was dead keen on action shots of James and there were no better images of interwar time trialing. So ferocious at the pedals, James would sometime break his toenails against the toe clips and Charlie Davey custom made special clips with bars at the front to prevent this.

|

| Cycling contributed this excellent resume of Bert James at the time he signed with Raleigh Sturmey Archer in October 1936. credit: Cycling, courtesy Peter Jourdain |

CHARLES HOLLAND (1908-1989)

Midland Cycling & Athletic Club

Charles Holland was the most versatile member of the team, one of the first British riders to prove himself in mass start racing, including being the first to compete in the Tour de France. His four brothers were all athletes and two were keen cyclists as was his father. Holland competed in his first race in 1927 and had his first win in a 10-mile event the following year. He soon thrived in international cycle competition. In 1932, he was picked to be on the British Olympic cycling team. Holland placed 15th in the road race, the last to be run as a time trial, and the British team placed fourth overall, as well as the team pursuit track event, Britain placing 3rd. Riding on the British team at the 1934 World Championship road race in Leipzig, he placed fourth. Holland represented Great Britain in the 1936 Berlin Olympics in the 100 km road race (the first in the Olympics run as a mass start race) and in the sprint finish, Holland finished 5th. That year, which Holland said was the peak of his career, he won the first massed start race in the British Isles, on the Isle of Man. He rode a Hercules with a Cyclo derailleur on this, averaging 22 mph on the 37-mile course. Yet, he still excelled at the classic British time trial and capped 1936 by winning the British Best All-Rounder award based on the best speeds over 50-, 100-mile and 12-hour time trials.

Bill Mills, editor of The Bicycle, described him as:

The best all-rounder, not in its narrow sense of best average in certain particular road events, but in its real sense of best at all types of cycling. Holland's record for the year includes successes at almost every possible type of racing: time trials, massed-starts, track racing, in fact the full programme in which every clubman likes to indulge. The specialist 'pot hunter' may confine himself to his little round of events at distances that he finds brings in the rewards, but the real clubman runs through the gamut of events, taking pleasure, if not prizes, in all and sundry. Of such a type is the dusky Midlander, taking all the sport can offer in his stride.

It was this true "all rounder" quality and international presence that made Holland one of the biggest names in British cycling and among the general public, outside of the narrow "clubman" fraternity. And, he had experience and results in the nascent mass start cycle racing that was beginning to grow in Britain even if still banned on open roads. Coming off his peak year and aged 30, Holland was ripe to become a professional and extremely attractive to sponsors due his national and international recognition.

On 25 April 1937 Holland signed with Raleigh Cycle Co./Sturmey-Archer Gears as a professional to ride in the Six-Day Race at Wembley that May. Holland was, with Frank Southall, the best-known British road cyclist, and his joining the Sturmey-Archer squad was a huge coup for Charles Marshall.

Under the terms of the contract, Holland wouldn't start riding for the team until that autumn allowing him to ride in Coronation Six-Day Race at Wembley paired with the Belgian, Roger Deneef. It wasn't a good event for the Midlander who crashed several times and on the second day he crashed again, broke a collar bone and dropped out. Holland broke the same collar bone in June when he tripped on a rabbit hole and had to miss riding with Continental stars on the motor-racing circuit at Crystal Palace, south London.

That same year he made history as the first Briton to compete in the Tour de France, although his injuries had curtailed his training for the race. Holland was part of three-man "British Empire" team of two Britons and a Canadian, and only Holland made it past Stage Two. With no support whatsoever, he had to abandon after stage 15 after he punctured, had no remaining spare tyres and his pump broke. It would be another 18 years before another Briton competed in the tour.

But the French, as much as the English, loved an underdog and Holland's plucky performance and engaging character endeared him to the extent he was perhaps more remembered than the winner of that year's Tour. For a true athlete, however, it was a bitter disappointment being let down by a total lack of support, manager or even the basic parts. After the Tour, Holland was Britain's most famous cyclist and one who, after this experience, probably appreciated the superb organisation and support Raleigh/Sturmey-Archer offered.

|

| Charles Holland first "Rode a Raleigh" during the Coronation Six-Day Race at Wembley in May 1937, the track version of the Raleigh Record Ace. |

|

| Charles Holland profiled in Cycling 29 January 1939. credit: Cycling, courtesy Peter Jourdain |

|

| Cycling, 26 January 1938: the Raleigh Team at the Addiscombe C.C. dinner, hosted by Charlie Davey who was co-founder of the club in 1924. credit: Cycling, courtesy Peter Jourdain. |

THOMAS (Tommy) EDWARD GODWIN (1912-1975)

Potteries CC & Vegetarian C&AC & Rickmansworth CC

The fact that he was a crack British cyclist and a vegetarian perhaps made it inevitable that Tommy Godwin found himself on the Raleigh/Sturmey-Archer team, its last new member and the youngest, too. But it was, in fact, a chance of opportunity, fate and a little luck that landed him. But in the end, it was, fittingly enough, largely because of a Sturmey-Archer hub.

Few get to place bets on a horse half-way through a race and few have paid off the way Godwin did for Raleigh, only to have most of the real promotional advantage soon lost and forgotten in the middle of a world war. Fortunately, Godwin's achievements have enjoyed a new discovery and appreciation today. For a team all about records and record breaking, his was the singular one for Raleigh/Sturmey-Archer or for any team for it remains, 77 years on, unbroken. His sponsors have sadly left Britain, but Godwin's all-time mileage record remains enshrined in the annals of national cycle sport achievement.

Godwin was born in 1912 in Stoke-on-Trent and aged 14, using his heavy delivery bike, less the front basket, from his first job for a local grocer, won his first cycling time trial, a "25" in 65 mins. In 1926 he joined the Potteries Cycling Club and continued to pile up wins on the time trial circuit including four "25s" done in under 1 hour 2 mins and clocking 236 miles for a 12-hour run. His average speed of 21.255 mph earned him a very respectable 7th place in the 1933 British All Rounder standings.

In 1911, Cycling began a competition for most 100-mile rides in a single year. The winner was Marcel Planes with 332 centuries in which he covered 34,366 miles. Like the R.R.A. records, this contest appealed to cycle companies eager to prove the mettle of the machine used as much as the man and reached a high level of competitiveness, again like the R.R.A. records, in the mid to late 1930s. The record was won nine times up to 1939. And like so many cycling records, it was presently held by an Australian, Ossie Nicholson, with 62,658 miles ridden in 1937.

So it was that Tommy Godwin and A.T. Ley, owner of a small cycle shop in Middlesex, conspired to be among the three entrants for the record in 1939. In October, Godwin took the major step of becoming a professional whilst Ley laid plans for new racing machines built around the Godwin attempt as well as making the "T.G. Special" that he would ride. It was, from the onset, a curious partnership in that Ley was a very small local concern rather the one of the big national cycle companies that normally sponsored these record efforts including for 1939, New Hudson backing Bernard Bennett from their home town of Birmingham.

Godwin started his run for the record on New Year's Day 1939 outside Ley Cycles in Northwood Hills, Middlesex before a crowd of some 200 cycling enthusiasts, record breaking cyclist Billie Dovey and Capt. George Eyston, holder of the world's land speed record. Godwin was after miles, not speed, but the going was hard as that winter was especially harsh and January and February disappointing mileage-wise.

Then came new opportunity in terms of contacts from Sturmey-Archer, a new hub gear and a renewed chance to renew his efforts with the coming of spring and fresh prospects. Raleigh/Sturmey-Archer was about to acquire its latest and great recordbreaker of them all.

|

| Godwin's run for the world's mileage record attracted scant press coverage at the onset and the most detailed report (left) came from Australia, The Worker, Brisbane, 10 January 1939. |

THE HUB OF RACING RECORDS

S.H. (Sid) Ferris

There would have been no Raleigh/Sturmey-Archer team and no frenzy of British road record breaking in the later half of the 1930s were it not for a machine. And not the bicycle, but rather the gears that both propelled it and the marketing and promotion that inspired the creation of the first Raleigh racing team. It "wasn't about the bike", but rather all about-- the hub gear. And a see-saw battle between it and the derailleur played out on the roads of Britain right up to the war, and in one case, nine months into it.

The most important event in the history of the Raleigh Cycle Co., other than its founding, was its fostering development of the multi-speed hub bicycle gear by Henry Sturmey and James Archer in 1902 and setting up a wholly owned subsidiary, Sturmey-Archer Gear Co., to manufacture it. The first Sturmey-Archer three-speed hub proved more than "the most important novelty of 1903" for it not only continued Raleigh's tradition of innovation and domination in the cycle trade, but wedded the fortunes of the company with the hub gear for the next 65 years. That entwining both made and ultimately hindered Raleigh as its dependence on the hub gear hindered rather than helped it in the 1960s-70s when the derailleur gear reigned supreme.

The original hub gears were wide-ratio three-speed ones, ideal for the general use machines at the heart of the Raleigh line-up. But, with the tremendous growth of "club" and competitive road sport in Britain after The War, Raleigh, too, began to cater to this market with the North Road Racer (1925), Club Raleigh (1927) and Record (1930). They were selling the club machines, but not the Sturmey-Archer hubs to go with them.

The original hub gears were wide-ratio three-speed ones, ideal for the general use machines at the heart of the Raleigh line-up. But, with the tremendous growth of "club" and competitive road sport in Britain after The War, Raleigh, too, began to cater to this market with the North Road Racer (1925), Club Raleigh (1927) and Record (1930). They were selling the club machines, but not the Sturmey-Archer hubs to go with them.

Competitive road cycling in Britain, dominated by the individual time trial when mass start road racing was banned on British roads, was not yet torn between the hub gear or derailleur gear. Indeed, the "clubman" disdained gears of any sort, preferring the classic fixed-gear with two-sided rear hub with two different sized cogs so that the wheel could be "flipped" when a gear change was needed. The size of the cogs were usually very close to each other i.e. 14t and 16t and suited the fixed wheel cycling style of an even pedal stroke and cadence that time trialing was all about. And for which the existing wide-ratio hub gears and early derailleurs were unsuited.

Nothing sold racing bicycles better than their association with competitive cycle sport which, in Britain at the time, was time trialling and competing for the R.R.A. (Road Record Association) point-to-point, mileage and distance individual records. Cycle companies would sponsor riders to "have a go" at the classic runs like London-Edinburgh, the 24-hour, 1000-mile and especially Land's End-John O'Groats. So, as Harry Green did for Raleigh and Sturmey-Archer back in 1908, so did Jack Rossiter in 1927 to inaugurate a remarkable decade of record-breaking runs to popularise both the cycle and the hub gear.

Concurrent with the new Raleigh Record model in 1930, Sturmey-Archer sought to tap into the growing cycle sport market with a new range of closer ratio hubs. Rossiter had used a wide ratio K hub on his record, ride, but what was really needed for time trialling was a closer ratio unit. Charles Marshall (Vegetarian C&AC) undertook his own tweaking of the existing K unit to achieve closer ratios starting in 1930. One of these hubs was used in his record breaking London-Bath-London ride 8 July 1931 and development was continued by Sturmey-Archer engineers.

Concurrent with the new Raleigh Record model in 1930, Sturmey-Archer sought to tap into the growing cycle sport market with a new range of closer ratio hubs. Rossiter had used a wide ratio K hub on his record, ride, but what was really needed for time trialling was a closer ratio unit. Charles Marshall (Vegetarian C&AC) undertook his own tweaking of the existing K unit to achieve closer ratios starting in 1930. One of these hubs was used in his record breaking London-Bath-London ride 8 July 1931 and development was continued by Sturmey-Archer engineers.

In 1932, the two new racing/club hubs, the close ratio KS (12.5% reduction/11.1% increase) and the medium ratio KSW (16.6% reduction/14.3% increase) were introduced. With racing in mind, every effort was made to reduce weight and they were the first S/A hubs with easier to change sprockets, wingnuts for easy wheel changes without disturbing the cone adjustments. These represented the most that could be accomplished with the original single stage epicyclic hub design.

THE STURMEY-ARCHER AR HUB (1936-42)

The speed man is exceptionally well served with this close-ratio three-speed gear, for one secret of sustained fast riding is a reasonably uniform pedalling rate so that muscles moving in rhythm are not suddenly jerked to another output rate. This is generally, the aim of all gearing on a bicycle. When the going is hard, due to gradient or wind, the riding pace is slowed, but the pedalling is maintained by dropping to a lower gear, whereas when the conditions are easy (say, along a level road with the wind behind) the cycling speed is increased as the top gear is snicked with the feet still rotating at approximately a normal gait.

Cycling

Under the leadership of William Brown, who took over Sturmey-Archer's development and design department in 1935, and in cooperation with Charlie Marshall, new racing specific hubs were developed, the first of which was the AR Ultra Close Ratio.

First marketed in November 1936, it offered what had long been sought by time-trialists and long distance racers, an ultra close ratio gear (7.24% increase/6.76% decrease) equal to adding or subtracting one-tooth from the sprocket and allowing a uniform pedalling rate against wind or gradient. Sprockets were available from 14 to 20 teeth. The AR hub weighed 2 lbs. 9 oz. and the net weight was offset by the deletion of the conventional rear hub and cogs.

THE STURMEY-ARCHER AM HUB (1937-42)

Introduced in late 1937, the AM was a medium ratio hub for general club riding and massed start racing, then just coming into the fore in Britain. The top-gear was a 15.55% increase over normal and the bottom was 13.46% reduction or equal to a two-tooth differential in the hub sprocket compared to the one-tooth difference of the AR. It was an extraordinarily useful range and the AM is still regarded as perhaps the best overall racing/club hub Sturmey-Archer made. Indeed, except for 1942-47, it was in continual production until 1958. This was sold from the onset with the trigger shifter and quick release cable fitting as standard.

THE STURMEY-ARCHER AF HUB (1939-42)

Announced in March 1939 and available the following month, the AF was groundbreaking for Sturmey-Archer being its first four-speed hub. Designed for time trialling and "fast work", it was in terms of ratios, the AR hub with an added bottom gear representing a 23% reduction from normal. Finally, the clubman had a hub gear to tackle hilly routes and headwinds and one that actually weighed a few ounces less than the AR.

|

| Credit: Sturmey-Archer Heritage.com |

Announced in November 1939, this was the only new hub Sturmey-Archer introduced during the war, but its production was so curtailed by the switch to wartime munition work, that very few were made. It is certainly one of the rarer hubs today but of course was widely popular in slightly updated form after the war. First gear (the lowest) offered a substantial 33½% decrease from normal low gear, 2nd was 14½% lower, 3rd was direct drive and 4th (the highest) was a 12½% increase over normal.

|

| Cycling, 8 November 1939 |

THE RECORD RALEIGHS

|

| The 1936 model of the Raleigh Record Ace was featured on the cover of Cycling's 27 November 1935 Cycle Show number. |

Here, indeed, it "wasn't about the bike" and the team was all about proving and promoting the Sturmey-Archer hub gears. The riders even signed with Sturmey-Archer Gears Ltd. not Raleigh Cycle Co. The advertising, too, throughout 1936 and 1937 was entirely by and for Sturmey-Archer with scant mention of the bicycle except perhaps a vague reference to "riding a Raleigh".

This subordination of corporate parent to offspring reflected an appreciation that the potential market for the hubs was greater than a specific bicycle brand or model, especially among clubmen who preferred smaller bespoke brands and would most likely be refitting their existing machines with the new hub gears. Indeed, Raleigh's own top racing/club machine, the Raleigh Record Ace, was sold with fixed/free gears as standard and Sturmey-Archer hub gears were an extra cost option.

It wasn't until 1938 that Raleigh began to run its own parallel promotion of its bicycles in connection with the team's records and before the year was out, had developed a new bicycle for mass start racing named after Charles Holland which had as standard fit, the Sturmey-Archer AM hub.

Even so, all of these records were indeed won on Raleigh bicycles and "real" ones, too-- off the shelf bog standard Raleigh Record Aces and Charles Holland Continentals.

1936-40 team racing bicycle

For the real enthusiast there is but one mount-- the Raleigh Record Ace. Light, fast, strong, and as the specification reveals, lavishly equipped, it is the perfect example of what a racing machine should be. In it, Raleigh design and craftsmanship reach their finest expression.

Raleigh catalogue, 1937

|

| The Raleigh Record Ace as portrayed in the 1936 catalogue. credit: ThreeSpeedHub.com |

Not entirely by coincidence, the Raleigh Record Ace or RRA had the same initials as the Road Record Association, the governing body of British cycle time trial and long distance road records. The name association between the two RRAs took on more meaning when the Raleigh machine, the top of the range, was the obvious mount for the new team.

The Raleigh Record Ace was introduced in late 1933 for the 1934 model year and was essentially the former Record model with the rear triangle and fork blades made of HM Steel (the forerunner to Reynolds 531) instead of Molybdenum steel which was still used in the main frame triangle. In 1936 the angles were changed from 67°/67° parallel to 71°/71° parallel and the following the year the front forks were chrome-plated and the cranks fluted.

There were very few alterations made to the RRA for team use other than colours. Saddle and 'bar choice was to individual preference. When announcing Ferris's signing with Sturmey Archer in October 1936, Cycling added that "he has already accepted delivery of his new Raleigh Record Ace models. They have 21-in. frames and are finished in flamboyant green with chromium-plated forks. The specification includes Brooks B17 Flyer saddle, 15-in by 4-in Marsh bars; and 26-in by 1⅛-in Conloy rims with Dunlop no. 3 tubulars...." The Conloy sprint rims were already an option for the general market machines. All of the team usually rode machines with sprint rims and tubular tyres with the exception of Tommy Godwin who rode the standard wheelset with Dunlop Sprite wire-on tyres.

Ferris was quoted as riding a 21" frame, James appears to be riding a 20", Holland rode a 22" and Godwin a 21".

There appears to have been no team livery and the machines were painted to rider preference with Bert James most photographed riding what looks like a pale metallic blue with darker blue seat tube/down tube/head panels and Ferris on his green RRAs. Holland rode what looks like a conventional black RRA and Godwin rode one of these in addition to a white or ivory-coloured one.

With an AR hub, such a machine weighed just shy of 24 lbs. and that was pretty much typical for the era.

The RRA was a reasonably light, strongly built and responsive machine for its era and ideal for time trialling and fast road work. By 1940, however, it had been overtaken by lighter machines with all Reynolds 531 frames and were it not for the war, it, too, would have been upgraded to all Reynolds 531 frameset before much longer.

Full details on the Raleigh Record Ace can be found here:

http://on-the-drops.blogspot.com/2016/12/raleigh-record-ace-rra-1933-1942.html

RALEIGH CHARLES HOLLAND CONTINENTAL (CHC)

1938-40 used by Charles Holland

I was delighted to have the opportunity of an entirely free hand in the designing of this new Raleigh model which bears my name. It incorporates all the points that experience on the road has taught me are essential for the Clubman's 'perfect' mount, and I recommend it wholeheartedly to my fellow riders.

Charles Holland, Raleigh-Sturmey Archer Professional Rider.

|

| Raleigh leaflet on the new Charles Holland Continental dating from the 1939 national Cycle Show, Earl's Court, September 1938. |

Few cyclists have won road records or races on a bicycle bearing their own name, and to Charles Holland's other accomplishments was added this extra laurel when, in late 1938, Raleigh introduced its first bicycle built especially for mass start racing, the Charles Holland Continental.

A variation on the RRA and employing the same mix of Molybdenum tubing in the main triangle and HM tubing in the rear triangle and fork blades, it featured more upright 71° seat/73° head angles and a Russ pattern front fork, Pelissier bend 'bars on a 3" extension and came with a Sturmey-Archer AM hub gear as standard. Like the RRA, it could be run with the stock 26" x 1¼" wire-on Endrick rims or 27" (as 700 wheels were called then) sprint rims with tubular tyres. Holland used the later on all his records. The livery a medium blue lustre.

Holland won his final two records on the machine and for the first time, Raleigh promoted the bicycle as much as they did the hub gear. The "CHC" had every promise of being a most successful part of the expanded Raleigh sports/racing range, but like so much the war curtailed it all. It did, however, form the basis for the post-was Raleigh Record Ace.

|

| Charles Holland poses on his Raleigh Charles Holland Continental. |

Full details on the Raleigh Charles Holland Continental can be found here

http://on-the-drops.blogspot.com/2017/03/raleigh-charles-holland-continental.html

THE RALEIGH RECORDS

14 October 1936

London-Edinburgh (disallowed)

S.H. (Sid) Ferris

Raleigh R.R.A. w. Sturmey-Archer AR hub

The first effort by Sturmey-Archer to crack an R.R.A. record was an exercise in great effort and greater futility, coming up against both wind and rule technicalities.

Sid Ferris decided to ambitiously attack two records simultaneously: London-Edinburgh (386 miles) which was presently held by E.H. Brown (1931) and the 24-hour record held by Hubert Opperman. It was also decided to tack on the extra time/mileage of the '24' at the beginning of the run so that Ferris commenced his ride 68 miles from Edinburgh at Glenogle Halt Gate.

Setting off on 14 October 1936, Ferris contended with the late season conditions including the shortening daylight with 13 hours of the ride having to be accomplished in darkness. Worse, the weather proved unkind that day with cross and head winds and rain for much of it. In the end, Ferris failed to break the 24-hour record (440 miles vs. 461¾ but had thought his 21-hour 28-minute time had clinched the Edinburgh-London one, averaging some 18 mph for the journey.

from Cycling 21 October 1936:

Making his first professional attempt on record on behalf of Sturmey-Archer Gears, Ltd., S.H. Ferris, the well-known Vegetarian, rode from Edinburgh to London in 21 hrs. 28 mins, beating the previous time put up by E.B. Brown, Wessex R.C., in 1931, by 21 mins.

The ride started at Glenogle Halt Gate, 68½ miles north-west of the Scottish capital, for Ferris had planned to attack Opperman's 24-hour record of 461¾ miles as well, and preferred to do the majority of the extra miles at the commencement. But the promised north-west wind failed to mature and, indeed, when air movement became noticeable in the last 100 miles of so of the journey to London it was a southerly rather than a northerly quarter and, in consequence, hindered instead of helped.

In the 24 hours Ferris covered 439.6 miles and when he reached London he had done 455.1 miles in 25 hrs. 56 mins. His starting time from Glenogle was 5 a.m. on Tuesday morning [14 October] of last week, and he left Edinburgh at 8.28 a.m., 13 mins. behind schedule. This 3 hrs. 28 mins. must, of course, be deducted from his total riding time to ascertain the new Edinburgh-London record figures.

No Wind.

The excellence of Ferris's ride is only emphasized by the lack of favourable breezes. It must be noted, too, that of the 25 hours awheel Ferris had to ride through 13 hours of darkness. Furthermore, from Thorne (8.7 p.m.) to London (5.56 a.m. Wednesday), a distance of 169 miles, his only eye troubled him seriously and it was afterwards found to contain grit.

He had only six stops throughout the whole ride, losing directly thereby 18 minutes. At Edinburgh he had to wait two minutes for Mr. W.S. Tait, the timekeeper, to come up and restart him at the exact minute. The level-crossing gates were against him at Snaith, where he had to wheel his machine through the small gates. At Thorne he stopped three minutes for a feed and a Grantham he changed machines to a lower series of gears. There was another feed (6 mins.) at Girtford, and he experienced his only puncture at Finchley, almost at the end of his task.

Some of the more notable times and distances are as follow:-- 50 miles, 2 hrs. 28 mins.; 100 miles, 5 hrs. 6 mins; 200 miles, 10 hrs. 25 mins.; 12 hours, 230 miles; 300 miles, 15 hours 50 mins.; 400 miles, 21 hrs. 30 mins.; 24 hours, 439.6 miles.

Ferris had scheduled to cover 463 miles in 24 hours to beat record by 1¼ miles) and had he maintained this pace he would have done 20 hrs. 9 mins. for the Edinburgh-London trip.

Here are some intermediate times of interest:-- Coldstream (116 miles), 5.52 (9 mins behind schedule); Newcastle (176) 9.6 (12 mins. behind); Darlington (209), 10.55 (17 mins behind); York 257½ miles), 13.28 (23 mins. behind); Grantham (343¾ miles), 18.16 (48 mins. behind); Girtford (406¾ miles), 22.2 (1 hr. 13 mins. behind).

These times reckoned from Edinburgh instead of Glenogle read as follows:-- Coldstream (47½ miles), 2.24; Newcastle (108½ miles), 5.38; Darlington (140½ miles), 7.27; York (189 miles), 10 hrs; Grantham (275¼ miles), 14.48; Girtford (338¼ miles), 18.34. Twelve hours after leaving Edinburgh Ferris had covered 224 miles miles from that city, but, of course, he had done an additional 68½ miles and been riding for 3 hrs. 28 mins prior to his arrival at Edinburgh.

The only section of the whole ride done at 'evens' was the first three hours, which did not count within the record claimed. He then did three hours at 19s,; 8 at 18½; 4 at 18; 3 at 17½; 2 at 16 (including the Girtford stop), and finished at 17s.

He was riding a Raleigh R.R.A. model equipped with the new racing close-ratio Sturmey-Archer three-speed hub. Up to Grantham his gears were 74.3, 79.7 and 85.5. There he changed to another machine with 72.7, 78 and 83.7.

Ferris had scheduled to cover 463 miles in 24 hours to beat record by 1¼ miles) and had he maintained this pace he would have done 20 hrs. 9 mins. for the Edinburgh-London trip.

Here are some intermediate times of interest:-- Coldstream (116 miles), 5.52 (9 mins behind schedule); Newcastle (176) 9.6 (12 mins. behind); Darlington (209), 10.55 (17 mins behind); York 257½ miles), 13.28 (23 mins. behind); Grantham (343¾ miles), 18.16 (48 mins. behind); Girtford (406¾ miles), 22.2 (1 hr. 13 mins. behind).

These times reckoned from Edinburgh instead of Glenogle read as follows:-- Coldstream (47½ miles), 2.24; Newcastle (108½ miles), 5.38; Darlington (140½ miles), 7.27; York (189 miles), 10 hrs; Grantham (275¼ miles), 14.48; Girtford (338¼ miles), 18.34. Twelve hours after leaving Edinburgh Ferris had covered 224 miles miles from that city, but, of course, he had done an additional 68½ miles and been riding for 3 hrs. 28 mins prior to his arrival at Edinburgh.

The only section of the whole ride done at 'evens' was the first three hours, which did not count within the record claimed. He then did three hours at 19s,; 8 at 18½; 4 at 18; 3 at 17½; 2 at 16 (including the Girtford stop), and finished at 17s.

He was riding a Raleigh R.R.A. model equipped with the new racing close-ratio Sturmey-Archer three-speed hub. Up to Grantham his gears were 74.3, 79.7 and 85.5. There he changed to another machine with 72.7, 78 and 83.7.

“The splendid performance of S.H. Ferris, latest recruit to the ranks of Nottingham’s ‘star’ cyclists, in beating (subject to EEA confirmation) in the early hours of this morning the national Edinburgh-London record for unpaced road riding is expected to bring a new phase of prosperity to the works of Messrs. Sturmey-Archer Gears Ltd.. Ferris, who is riding professionally for this Nottingham concern, is expected to attach further records next year. His object is to emphasise the greater efficiency of the product of the British gear industry against many foreign types of chain gears which have invaded the country in recent years” Nottingham Post, 14 October 1936

|

| Press cuttings prematurely heralding Ferris's breaking the Edinburgh-London record. |

But alas, it was not to be for in December, the R.R.A. rejected Ferris' claim to the record owing to a technicality: his leading support car "failed to maintain the stipulated distance of 100 yds." (a rule designed to prevent pacing) over a substantial portion of the ride. This was appealed and the rules later changed, but the record books remained unaltered and the following June Ferris officially broke the Edinburgh-London run and by a greater margin.

|

| credit: Feed Well- Speed Well, Oxbow |

25 May 1937

London-Portsmouth

H. (Bert) James

Raleigh R.R.A. w. Sturmey-Archer AR hub

The first R.R.A. record to be broken by the Raleigh/Sturmey-Archer team, London-Portsmouth round trip, was by Bert James on 25 May 1937 with a time of 6 hours 33 minutes 57 seconds. James had beaten Australian F. Stuart's previous record, held for two years, by a scant 10 seconds, the narrowest margin of victory for an R.R.A. record to date.

"It was a magnificent effort," said manager Charlie Davey, "Then, when over fifty miles from home on the return journey, James had a puncture. This was followed seven minutes later by another. Then he actually had to slow up for a few seconds, owing to traffic. In the following car we had almost given it up for hopeless, but in the last two hours we saw the most tremendous fighting effort any of us have ever seen, and James pulled up across the line with seconds in hand. At the end of the trip James looked surprisingly fresh, and the first thing he did was to send a telegram to his wife."

from Cycling 2 June 1937

The Story of a Magnificent Fight Against Wind and Punctures

Although delayed more than three minutes through two punctures, H. James, the plucky little Welsh professional, broke his first national bicycle record early on Tuesday [25 May] of last week when he rode from London to Portsmouth and back in 6 hrs. 33 mins. 57 secs.-- 10 secs better than the previous record put up by W.F. Stuart, of Australia, in 1935. This is narrowest margin by which any national has ever been beaten of the whole 50 years of the Roads Record Association, yet this in no reflects upon the greatness of James's ride, for Stuart's effort was a sterling record (beating as it did F.W. Southall's record by 15 minutes); rather does it add further glory to the epic account of one of the finest and pluckiest performances ever listed upon the books of the association.

Herbert James has been dogged with ill-luck ever since he turned professional in October of last year, and this was his second attempt upon Stuart's figures. The ride was timed and observed practically throughout by Mr. R.W. Best, the famous R.R.A. timekeeper, who has timed more road records than any other man living, and when Mr. Best gave him the signal to go at 2 a.m. on Tuesday, the morning was warm and cloudy, the prospects being of a faint wind would spring up later to assist him from Portsmouth. As is often the case the weather prophecy was inaccurate. The journey from the start at the 14th milestone, to Hyde Park Corner (where he turned after 33½ mins.-- half a minute slower than schedule) was almost in a dead calm, but soon after he had repassed the starting point, heading towards the sea, a strong cross breeze sprang up, sending the clouds scudding across the sky, and causing James's advisers some apprehension.

James, however, using his gears of 74-79-84, continued to ride strongly and, after covering 22 miles in the first hour, reached Guildford (38⅓ miles) four minutes outside a schedule planned to beat record by five minutes. Two heavy showers of rain had not perturbed him, and although it as still raining as sped down Guildford's steep and famous, but now deserted, High Street, the big yellow moon was peeping bravely through the heavy clouds.

Dawn came as James began the ascent of Hindhead. Up he climbed at a steady 18 miles and hour, the win, now nearly due south, blowing stronger. Half a mile below the top of this famous beauty spot James had covered the first 50 miles in 2 hrs. 24 mins (the first 25 miles in 1 hr. 9 mins.), but he had little time to admire the fine view of Surrey scenery spread below, nor the beauty of the shining moon hanging in a pale bluish sky of early morning, and down the other side he pedalled at brisk speed until a puncture in the back tyre caused his first dismount.

Quickly another machine was unstrapped from the following car and, delayed by a minute and a half, James rode hurriedly on his way again. Seven minutes later he punctured again-- in the back tyre. This time no machine was readily available, the official car having been slightly delayed, and impatiently James had to wait more than two minutes before the car screeched up with another bicycle, Yet, notwithstanding the delays, James reached Petersfield only three minutes outside schedule, having covered nearly 63 miles in the three hours.

There was still no sign of the wind veering round to south-west as required for the return journey from Portsmouth when James negotiated the early traffic, with a longer route than usual owing to market day regulations, to the Post Office in the famous seaport; but the plucky Vegetarian kept plugging away hopefully.

He turned at Portsmouth two and half minutes behind schedule, having covered the 80¼ miles in 3 hrs. 52½ mins, with the wind on the his side and the strong sun dazzling in his eyes, yet he rode determined to get the record, and by the time he reached Petersfield, having climbed Butser at a steady 13 miles an hour, he had reduced his arrears on schedule to within a minute and a half. He had covered 100 miles in 4 hrs. 48 mins. Then his bad time set in. The next 19 miles up to the top of Hinehead were miles of suffering, and when he reached the summit he had fallen three and a half minutes behind, and the prospects of the record were beginning to fade. But the Welshman was not done yet. He had 27½ miles to go and 72 minutes in which to do it to beat record by seven seconds-- and James gripped firmly his handlebars and trod hard on the pedals. An hour from the end 22 miles still remained to be ridden-- the same number of the miles he had ridden in the first hour-- and now he was tired after more than 115 hard miles.

At Guildford (122 miles) he was exactly five minutes behind schedule, running almost dead level with the record, but the wind was still sweeping across the road, and it looked as though James, in view of the weather, was not to gain the coveted honour, but he still struggled gamely, faced with the prospect of having to cover the last five miles in 13½ minutes. The traffic by now was beginning to hinder him, and although he swept through Esher pedalling franactically at 28 miles an hour, cars and lorries were causing concern to his followers. Yet he just did it. Ten seconds before the time was up James sped past the little group that waited anxiously at the milestone-- and one of the first to congratulate him was a sporting policeman. Well done, James, a plucky ride! This was the first record beaten by a professional since Stuart and Milliken, of Australia, best the York to Edinburgh and "12" tandem records in 1935.

James was handed a drink of Emprote, or orange juice and honey, or grape juice and honey, or lemon juice and honey every 12 miles. The whole arrangements for the record were in the hands of James's manager, Mr. C.F. Davey, who held the record himself 11 years previously. James rode a bicycle equipped with a Sturmey-Archer three-speed gear.

Dawn came as James began the ascent of Hindhead. Up he climbed at a steady 18 miles and hour, the win, now nearly due south, blowing stronger. Half a mile below the top of this famous beauty spot James had covered the first 50 miles in 2 hrs. 24 mins (the first 25 miles in 1 hr. 9 mins.), but he had little time to admire the fine view of Surrey scenery spread below, nor the beauty of the shining moon hanging in a pale bluish sky of early morning, and down the other side he pedalled at brisk speed until a puncture in the back tyre caused his first dismount.

Quickly another machine was unstrapped from the following car and, delayed by a minute and a half, James rode hurriedly on his way again. Seven minutes later he punctured again-- in the back tyre. This time no machine was readily available, the official car having been slightly delayed, and impatiently James had to wait more than two minutes before the car screeched up with another bicycle, Yet, notwithstanding the delays, James reached Petersfield only three minutes outside schedule, having covered nearly 63 miles in the three hours.

There was still no sign of the wind veering round to south-west as required for the return journey from Portsmouth when James negotiated the early traffic, with a longer route than usual owing to market day regulations, to the Post Office in the famous seaport; but the plucky Vegetarian kept plugging away hopefully.

He turned at Portsmouth two and half minutes behind schedule, having covered the 80¼ miles in 3 hrs. 52½ mins, with the wind on the his side and the strong sun dazzling in his eyes, yet he rode determined to get the record, and by the time he reached Petersfield, having climbed Butser at a steady 13 miles an hour, he had reduced his arrears on schedule to within a minute and a half. He had covered 100 miles in 4 hrs. 48 mins. Then his bad time set in. The next 19 miles up to the top of Hinehead were miles of suffering, and when he reached the summit he had fallen three and a half minutes behind, and the prospects of the record were beginning to fade. But the Welshman was not done yet. He had 27½ miles to go and 72 minutes in which to do it to beat record by seven seconds-- and James gripped firmly his handlebars and trod hard on the pedals. An hour from the end 22 miles still remained to be ridden-- the same number of the miles he had ridden in the first hour-- and now he was tired after more than 115 hard miles.

At Guildford (122 miles) he was exactly five minutes behind schedule, running almost dead level with the record, but the wind was still sweeping across the road, and it looked as though James, in view of the weather, was not to gain the coveted honour, but he still struggled gamely, faced with the prospect of having to cover the last five miles in 13½ minutes. The traffic by now was beginning to hinder him, and although he swept through Esher pedalling franactically at 28 miles an hour, cars and lorries were causing concern to his followers. Yet he just did it. Ten seconds before the time was up James sped past the little group that waited anxiously at the milestone-- and one of the first to congratulate him was a sporting policeman. Well done, James, a plucky ride! This was the first record beaten by a professional since Stuart and Milliken, of Australia, best the York to Edinburgh and "12" tandem records in 1935.

James was handed a drink of Emprote, or orange juice and honey, or grape juice and honey, or lemon juice and honey every 12 miles. The whole arrangements for the record were in the hands of James's manager, Mr. C.F. Davey, who held the record himself 11 years previously. James rode a bicycle equipped with a Sturmey-Archer three-speed gear.

|

| Bert James at the end of his first record with his wife and left, Charlie Davey, and right, Sid Ferris. credit: Cycling, courtesy Peter Jourdain |

3 June 1937

Edinburgh-London

S.H. (Sid) Ferris

Raleigh R.R.A. w. Sturmey-Archer AR hub

A man not to be denied, at least a second time, Ferris's second effort at the Edinburgh-London record on 3 June 1937 was as much a success as the first in October 1936 had been a disappointment. With no attempt to also challenge the 24-hour record this time, Ferris rode the 378-mile course from the Scottish Capital to the British one in 20 hours 19 minutes, besting the previous record by E.B, Brown which had stood for six years by 1½ hours despite headwinds in Northumberland and Yorkshire.

from Cycling 9 June 1937

The Sturmey-Archer Professional Put Up Such an Apparently Effortless Performance that This Great Ride was almost Without Incident

S.H. Ferris, the well-know long distance Vegetarian rider, who last year turned professional and joined the Sturmey-Archer organization, set up a new record on Wednesday-Thursday last [3 June] when he rode from Edinburgh to London, a distance of 379 miles, in 20 hrs. 19 mins. It was really a splendid performance, beating the previous record (put up by E.B. Brown, of the Wessex R.C. in 1931, who clocked 21 hrs. 49 mins) by no less than 1 hr. 30 mins.

Ferris averaged nearly 18¾ miles an hour all the way, despite the fact that the wind, generally favourable from a northerly quarter, became erratic over the south Yorkshire area, and for a time actually opposed the rider.

He rode consistently throughout the trip with an ease that made the long trial appear almost effortless, and resulted in a performance that was virtually devoid of incident. Ferris schedule for the Edinburgh-London ride as 'training spin' for his attempt upon the 866-mile record from Land's End to John o'Groats which he is planning to make later this season. (The record is at present held by the famous Australian, Hubert Opperman, whose End-to-End times, set up in 1934, is 57 hrs. 1 min.)

When the Vegetarian dismounted at the G.P.O. London, 25 secs. before 3.19 a.m. last Thursday, he certainly looked fit enough for a further and longer session, such as will be demanded of him when tackles the journey from Cornwall to Caithness. He only regret was that he had not 'pipped' the tandem figures for the Edinburgh-London ride, which are only 1 min. faster than Ferris' time, and were recorded at 20 hrs 18 mins by A.R. Smith and F.E. Maston (North Road C.C.) early last year.

Ferris's machine was equipped with the new Sturmey-Archer A.R. ultra-close-ratio three-speed hub, providing him with gears of 74.3, 79.7 and 85.5. ins. He rode one machine throughout and had no mechanical or tyre trouble whatever.

It will be recalled that in October last Ferris did the same journey in 21 hrs. 28 mins, beating the record by 21 mins, but the R.R.A. rejected the claim, it having been proved 'that over a considerable portion of the course the following car failed to maintain the stipulated distance of 100 yds.' It was nevertheless, a sterling performance in adverse weather conditions. Owing to the lateness in the season, furthermore, Ferris had to contend with 13 hrs. of darkness and his eye troubled his seriously over the last 170 miles of the trip. This latest achievement, faster than the former by 1 hr. 9 mins, gives a truer measure of the stayer's ability.

|

| credit: Cycling, courtesy Peter Jourdain |

The schedule prepared for Ferris was an interesting one. He started at 7 a.m. on Wednesday and down to arrive in London at 3 a.m. on the Thursday, which made an elapsed time of 20 hours, average speed for the 379 miles of 19 m.p.h. As has already been stated, he was timed in at 3.19 a.m., 19 mins behind his schedule. The intermediate times, however, were notable in that the rider was called upon to do 21 m.p.h. for the first 202 miles (to Ferrybridge) and then 17 m.p.h. over the remaining 177 miles. By the time he reached Ferrybridge he was 43 mins. behind schedule, and anyone without the 'key' to the time-table might gained the impression that Ferris was going to beat the record by no more than an hour. But from that point he steadily raced his schedule and, regaining what were seemingly lost minutes, due the fast timing for the early stages, he finished only 19 mins down on his timetable, but, of course, 1½ hours better than the previous record. Ferris's averaged for the two sections of the journey were: -- Edinburgh to Ferrybridge 19.6 m.p.h. and Ferrybridge to London 17.7 m.p.h.

The rider stopped four times on the way. His first was at Aycliffe (132 miles), where a sit-down meal occupied 8 mins. Between Newark and Grantham he had two halts, one of a minute, where he sat across his machine to take a drink, and an arranged stop of 5 mins. for massage, wash and food. He was off the machine again at Girtford for 2½ mins., where he washed and ate.

He reached the exact half-way point, 189½ miles, in 9 hrs. 38 mins, and took 10 hrs. 41 mins for the second half of the journey. His first '100' was covered in 4.48½ and his final century in 5.29

|

| Cycling, 14 July 1937 |

17-19 July 1937

Land's End-John O'Groats

S.H. (Sid) Ferris

Raleigh R.R.A. w. Sturmey-Archer AR hub

Indicative of anticipation and appreciation for his own abilities and ambitions, Ferris' Edinburgh-London record was considered a mere "training ride" preparatory for tackling what had always been the biggest prize in British long distance time trialling-- Land's End to John o'Croats-- 860 miles from the western limits of England to the far north of Scotland. It was the British Tour de France in cycling endeavour and publicity. And for Raleigh and Sturmey-Archer, it held special meaning given that its present involvement in road cycle sport dated from Jack Rossiter breaking the record for the ride in August 1929 on a Raleigh Club with a Sturmey-Archer K three-speed hub gear, 21 years after Harry Green did so also on a Raleigh with a Sturmey-Archer hub gear. Now, in 1937, fittingly Raleigh's 50th anniversary, it was time again to prove the supremacy of Raleigh, Sturmey-Archer and the mettle of its new professional racing team.

No less importantly, the present Land's End-John o'Groats record was held by Hubert Opperman, the great Australian champion. An English road record held by an Australian was sufficient to stimulate the sports rivalry already existing between the two countries, but Opperman was riding for Raleigh's rival, BSA, and used Sturmey-Archer's great competitor, a Cyclo derailleur.

It was always to fall to Sid Ferris to undertake the ride, even if its distance and duration was far in excess of his previous records as Bert James was the more traditional "50-100" time trial man.

In an article in Cycling, 19 January 1938, Ferris described the arduous and extensive training and preparation for the epic ride:

Before I started from Land's End on what proved to be the record ride in the middle of July last year, I had nearly 4,000 miles of riding in my legs. This total included two 50-mile time trials on the Bath Road with Bert James in the early April, London to Land's End, and Land's End to Carlisle, occupying about five days. Here my training ride over the actual ride was halted, as my manager, Charlie Davey, with whom I was in daily touch, asked me to make for Edinburgh, from which the northern capital the following morning out on my successful record ride to London. Almost immediately after this 'speed test', I turned my wheels northward again, and going via Edinburgh to Carlisle continued on the End-to-End route to John o'Groats, this Scottish section of the ride occupying three days.

Throughout the journey from Land's End to Carlisle, and then later from Carlisle to John o'Groats, my machine was fitted with a revolution counter previously calibrated, and I noted down the intermediate distances between all the principal places en route. My manager and I had, of course, surveyed the course by car earlier in the season. When one notes what Menzies and the other year's record riders are doing daily I find it remarkable to compare my own daily trips of 150 to 170 miles undertaken on about 10 days only during this training period. For the rest of the time, including the fortnight at Land's End before the actual start, I did 30 miles day.

Incidentally, readers may be interested to know that I trained on the same gears as for the record itself, my Sturmey-Archer A.R. hub having a normal of 78 inches.

In an article in Cycling, 19 January 1938, Ferris described the arduous and extensive training and preparation for the epic ride:

Before I started from Land's End on what proved to be the record ride in the middle of July last year, I had nearly 4,000 miles of riding in my legs. This total included two 50-mile time trials on the Bath Road with Bert James in the early April, London to Land's End, and Land's End to Carlisle, occupying about five days. Here my training ride over the actual ride was halted, as my manager, Charlie Davey, with whom I was in daily touch, asked me to make for Edinburgh, from which the northern capital the following morning out on my successful record ride to London. Almost immediately after this 'speed test', I turned my wheels northward again, and going via Edinburgh to Carlisle continued on the End-to-End route to John o'Groats, this Scottish section of the ride occupying three days.

Throughout the journey from Land's End to Carlisle, and then later from Carlisle to John o'Groats, my machine was fitted with a revolution counter previously calibrated, and I noted down the intermediate distances between all the principal places en route. My manager and I had, of course, surveyed the course by car earlier in the season. When one notes what Menzies and the other year's record riders are doing daily I find it remarkable to compare my own daily trips of 150 to 170 miles undertaken on about 10 days only during this training period. For the rest of the time, including the fortnight at Land's End before the actual start, I did 30 miles day.

Incidentally, readers may be interested to know that I trained on the same gears as for the record itself, my Sturmey-Archer A.R. hub having a normal of 78 inches.

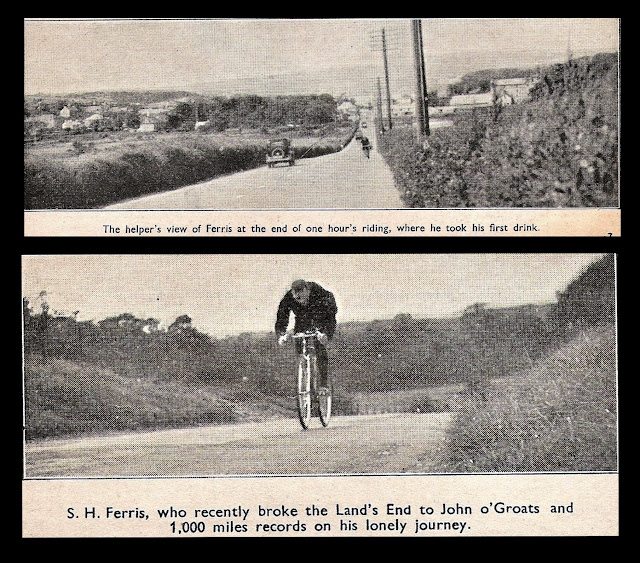

Leaving Land's End at 10.00 am on the 17 July 1937, Ferris reached Bodmin on schedule at 12.50 pm but was an hour down by the time Bristol was reached and no time made up by Lancaster after 403 miles. After Carlisle (470 miles), he was still 80 minutes down, but it was very fast running after that and upon reaching Inverness (728), Ferris was 30 minutes back and rode the remaining 142 miles to John O'Groats in 9 hours 33 minutes to reach there 57 minutes ahead of schedule. His total time for the 860 miles was 2 days 6 hours 33 minutes averaging 16 mph, beating Opperman’s time by 2 hours 28 minutes and standing for 21 years.

|

| credit: Cycling, courtesy Peter Jourdain |

from Cycling 21 July 1937:

In a great ride, the merit of which is amply proved by the lack of incident, S.H. Ferris, the Vegetarian professional, riding machines equipped with Sturmey-Archer close-ratio hub gears, copleted, over the week-end, the 870-mile journey from Land's End to John o'Groats in 2 days 6 hrs. 33 mins., beating the previous record set-up by Hubert Opperman, the Australian, in 1934, by 2 hrs. 28 mins. Ferris had no mechanical troubles and suffered only one puncture.

As for the man himself, this ride of twice the distance of his known staying capabilities stamps him as distance rider of world fame. Through the journey he rode strongly without any signs of distress. All but one stop were of duration for sitting -down feed, the exception being a halt of 37 mins. Near Blair Atholl where had actually scheduled to stop for an hour.

Ferris started at 10 o'clock on Saturday morning last and reached John o'Groats at 4.33 on Monday afternoon. He was scheduled to arrive there at 5.30 p.m. From John o'Groats, after a three-hours' halt for rest, he was due to leave on series of detours to complete the 1,000 miles, which record is held by Opperman in 3 days 1 hr. 52 mins. As we go to press we learn that Ferris may start on these last 130 miles with less than three hours' stop, as he is in such splendid condition.

Ferris's first attempt on the End-to-End record was made on Wednesday last, but a promised south-west wind failed to materialize and the Vegetarian started into a 20 m.p.h. opposing breeze. He rode only to the party's headquarters at Blackwater, covering the 31 miles in 1 hr. 47 mins. Here Manager Charlie Davey, called the attempt off.

Better conditions prevailed on Saturday last and at 10 a.m. Mr. B.W. Best signalled the time to start and Ferris got moving in splendid fashion.

It will be remembered that when Opperman did this ride in 1934 in addition to setting up new time for the End-to-End (2 days 9 hrs. 1 min.) he also broke the 24-record with 431½ miles. The Australian was very much slower during the second half of his ride, due to sickness which caused delays amounting to about two hours. This after covering 431½ miles in the first 24 hours (18 m.p.h.) he took 33 hours for the remaining 433½ miles (13 m.p.h.), making an average speed of the whole trip of just over 15 m.p.h.

Although he had scheduled for an attempt on the '24' record (which now stands at 461¾ miles) Ferris made out a timetable coinciding with Opperman's first day of riding and then planned beat 13 m.p.h. over the Scottish roads where the Australian's record was in fact beaten.

The Vegetarian was not favoured with quite good wind conditions as Opperman, however, whilst furthermore he is not so brilliant a pedaller for the part of a stayer's job as the Australian so that the Englishman got behind the schedule he had set himself to Kendal. Where Ferris showed to advantage, however, was in the later stages where he ability to plod without too great a loss of pace and with few stops brought him level with Opperman's times and then gradually showed a gain over the previous record figures.

The breeze on Ferris's back at the start was but slight, its right direction being the best recommendation. Penzance, 11 miles, was reached in 27½ mins. And Redruth (27) in 1 hr. 20 mins. So that the Vegetarian not only got inside his schedule at once, but was beating Opperman who took 28 mins. And 1.22 respectively to these points. By the time Bodmin (57) was reached, the wind had veered with north in it and Ferris was 1¼ mins. Behind his timetable and half a minute slower than Opperman, his time here being 2.51½. He made good going to Launceston (79), however, doing 3.55 compared with the Australian's 4.1, but at Okehampton (98), where he was scheduled to do 5 hrs., he was clocked 5.17 (Opperman 5.3)

|

| credit: Cycling, courtesy Peter Jourdain |

From that point to Bristol, and more particularly after Exeter where the road turned more northward, Ferris got behind the Australian, but better conditions prevailed after Bristol, the slight air movement coming from a helpful quarter. At Exeter (120) he was doing 6.37 against Opperman's 6.15 and he passed through Bristol (156) after 11 hours riding. This was at 9 p.m. on Saturday. His schedule time at Bristol was 8 p.m. Opperman on this ride had 10 hours 8 mins. To that city, between Bristol and Gloucester, when 210 miles had been covered, the 12-hour time elapsed, which total was exactly 15 miles fewer than Opperman's figures for 12 hours.

Then followed a period of most consistent riding. From Gloucester right up to North Lancashire, Ferris rode at his scheduled speed, preserving almost exactly the 50-55 mins he had lost. He was due at Gloucester (231) in 12 hrs. 10 mins; he took 13 hrs. 6 mins. His time at Worcester (257) was 14.32, 52 mins behind schedule, and at Whitchurch (321) he had been riding 18 hrs. 20 mins, 55 mins down on schedule. His time at Warrington (354) was 20 hrs. 9 mins., 49 mins behind timetable. Ferris was due at Preston (383) at 7 a.m., 21 hours after the start and he reached there at 7.49 a,m. with an elapsed time of 21.49 compared to Opperman's 21.5.

On the stretch from Carlisle to Lockerbie, where the route turns north-west, a west wind hindering the rider, but from that point a following breeze sprang up, which gave welcome aid to John o'Groats.

On the stretch from Carlisle to Lockerbie, where the route turns north-west, a west wind hindering the rider, but from that point a following breeze sprang up, which gave welcome aid to John o'Groats.

Interviewed at the finish, Ferris told reporters: "I am feeling very fit. I had a lot of rain on Saturday, and it was very cold cycling through Grampians on Sunday night. I am pleased that the run has been a success." His wife, who followed her husband in a car, added "It was a strain watching the clock all the way, but I am glad he broke the record. He had no sleep, and only short rests occasionally." After three hours rest at John O' Groats, Ferris was back on his RRA to make a run for the 1,000-mile record which he broke in a time of 2 days 22 hours 40 minutes, three hours faster than the previous mark.

|

| credit: Cycling, courtesy Peter Jourdain |

from Cycling 28 June 1937:

To say that Sidney Ferris's latest record is full of special interest is superfluous. No record over the End-to-End course could help being a feat of extraordinary interest, and now that that Ferris has beaten the figures made Hubert Opperman three years ago in a ride that was, rightly, the centre of tremendous glamour at the time, we must accord the limelight to Ferris and hail him as the outstanding long-distance rider of the day. My immediate concern is to examine Ferris's ride in which he came to bring off so successfully a coup which, notwithstanding the handicaps that barred Opperman's way, was nevertheless considered to be a task of fearful severity.

Let us recapitulate. Opperman rode from Land's End to John o'Groats and on for the 1,000 miles. He set up what was then a new 24-hour record of 431½ miles on the first day, and although his illness caused stops amounting to about three hours afterwards, he rode fast enough between stops to cut over four hours from Rossiter's record at Groats, afterwards reducing the 1,000-mile record by 10 hours, notwithstanding a six-hour rest at John o'Groats House.

|

| credit: Cycling, courtesy Peter Jourdain |

In setting out to beat the record the next man was faced with the problem of getting ahead by riding an even fiercer first 24-hours, and this taking more out of himself than he could spare, in view of the following ordeal, or of riding a shorter '24' and this entering Scotland well behind schedule, risking everything on the hope that his stamina and fortitude would enable him to dispense with the stops that Oppy made, and forge ahead in the latter part of the ride.

What Ferris did was to for both methods in part, but in practice the conditions prevented it. He could not do the first, but did the second. He was behind at the end of 24 hours, but his ride through Scotland was a tremendous performance, for he was over three hours faster than Opperman from Carlisle to John o'Groats.

On the first day, after working through a cross-win all the way from Land's End, Ferris became troubled when, after Exeter, he began to hit the wind three-quarters, late in the afternoon, and at Collumpton he actually stopped to discuss whether it was worth going on. At seven o'clock that evening he felt happier, although the win had not yet improved.

|

| credit: Cycling, courtesy Peter Jourdain |

Again, on the next day, the approach of afternoon and a close westerly wind heralded a long slow spell which, added to the stop of 16 minutes near Carlisle, caused him to enter Scotland behind record when he might have been ahead. The lag did not end there, and for many more miles through Gretna, Kirkpatrick and Ecclefechan he was worried. The wind hit him and the air stifled him, and after several short stops he made a halt of 12½ minutes between Ecclefechan and Lockerbie which he announced he would 'borrow' from his next scheduled stop. It was at this time that the sight of Ferris lying on the grass started a rumour, which spread along the road with remarkable celerity, that he had retired!# Complete was the transformation when, at Lockerbie, a welcome south-wester freshened, vivified the air, and began a blow that lasted to the very end of the road northward. Heavy rain over the Lammermuir hills quite refreshed him. From that time nothing went wrong with Ferris except a puncture near Dunblane and some lost time in Inverness. Having surveyed the route in detail some weeks earlier, he fancied he could improve on the usual way into Inverness, and he had everything planned. He threaded his way from one street to another, looking round for his followers, to whom he was then the sole guide of the road. Unfortunately, in the excitement, he made a wrong turn which to the loss of some 10 minutes. With that loss he had, however, already dropped behind record again. He had got inside Opperman's figures before Perth, and the 36 hour had given him a couple of miles more, and he had a further possible gain by Opperman's two lengthy stops at Blair Athol and Aviemore. But he did not ride the Grampians so slickly as did the Australian, and his own two stops, with slower speed, brought him outside the record when he left Aviemore, where had rested for a few minutes on one of the portable beds carrier in a following vehicle.

Ferris's time at the 800th mile was exactly 2 h. 28 m. faster than that of Opperman (which included one long stop, of course), and it was that margin by which he beat the record. However, the afternoon of that third day again found him listless, so that he was glad to revise his optimistic plan, formed when he was feeling 'good' a little earlier, to stop only an hour at Groats.

|

| Ferris's ride attracted national media attention both in Britain and Australia. credit: British Newspaper Archives and Trove, National Australian Newspaper Library |